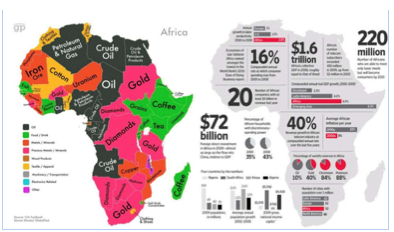

Africa has the potential to construct more wealth in the next 35 years, than the $1,3-trn it amassed in all of history.

This impetus will be driven by technological innovation that is enhancing intelligence, reducing costs and accelerating its performance capability to create value 10 times faster than 100 years ago. Between 1900 and 1990, the USA grew its GDP from $500-billion to $9-trillion in the same way.

With a forecast of 5.2% growth, an estimated $13-trn in extractable energy, a comparative advantage in solar energy, a young and fast-growing middle class, the rapid absorption of mobile connectivity and communication technologies enabling sophisticated tracking and interpretation of big data, Africa may double its economy every 12 years to reach $2,6-trn by 2027 (and $13-trn by 2050).

Africa’s wealth prospects

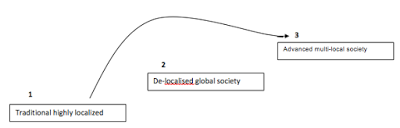

According to Prof. Ezio Manzini, one of Europe’s most eminent social innovation experts, Africa is poised to leapfrog from a ‘not yet fully industrialised’ economy into a hybrid, multi-local society.

Manzini argues that if first world innovation is applied to valorize Africa’s third world commodity base, it will by-pass certain stages of economic development to reflect a new form of post-industrial society with a different economic structure.

The Leapfrog Hypothesis

A shift towards an advanced multi-local society in a not-yet (fully) industrialized society

According to Professor Philip Spies, one of Africa’s leading futurists, Africa’s leapfrog requires a supportive innovation environment to enable such a future economy. This would blend endemic (human-centered) technological innovation with ‘technology transfer’ (artefact-centered innovation) in a way that strengthens rather than disrupts a community’s potential for development.

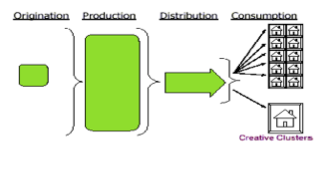

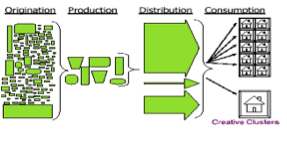

Global investors like Unilever, are already adopting this strategy in Africa with a multi-local, rather than multinational approach to sustainability on the continent. It is sourcing local products and using local people, embedding local values in the design and using first world technology to produce and distribute goods to market. In this way, technology transfer and diffusion of innovation has a far greater rate of success.

The structure of the Industrial economy in the developed world

The structure of Africa’s post-industrialised, multi-local economy

There is growing awareness that while first world technology will boost Africa’s intelligence, ensure greater quality, reduce labour costs through mechanising replicable actions and enable better monitoring, in the developed world it produced a regenerative industrial culture and marginalised the poor.

Therefore a host of educational and policy initiatives are underway to drive Africa’s transition to an innovation-led economy with supportive socio-economic conditions. In 2014 the African Union adopted the Science, Technology and Innovation Strategy for Africa (STISA).

This continental strategic framework focuses on six critical areas for socio-economic innovation:

- eradication of hunger and ensuring food & nutrition security;

- disease prevention and control

- and ensuring well-being;

- communication,

- live together- build the community and;

- wealth creation.

The changing structure of global trade, international architecture of finance and technological innovation in banking will have a profound impact on wealth creation in Africa.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts that in the next 10 years, six of the ten highest growing economies will be in Africa. Current FDI flows are around $60-billion a year boosted by the BRICS geo-political alignment encouraging greater trade with Brazil, Russia, India and China. The rate of return on foreign investment in Africa is higher than in any other developing region with almost three times the average multiple growth potential.

However, it is constrained by four major obstacles: a lack of access to formal financial services, weak infrastructure, a lack of funds for public investment and political instability in certain countries.

While agriculture and fishing accounts for two-thirds of jobs in Africa, they suffer the most from these obstacles. Currently, Africa is the least wealthy region with the lowest number of High Net Worth Individuals [HNWI] in the $52.5-trn global wealth system.

2013 Global Wealth by Region

| Rank | Region | Overall Wealth

USD trillions |

Annual

Change |

No. of HNWI (millions) | Annual

Change |

Forecast Growth Rate |

| 1. | North America | 14.8 | 16.6% | 4.3-m | 16.6% | 3% |

| 2. | Asia Pacific | 14.2 | 17.3% | 3.02-m | 25.8% | 7% |

| 3. | Europe | 12.3 | 12.5% | 3.83-m | 12.5% | .2% |

| 4. | Latin America | 7.7 | 3.1% | 0.45-m | 8.3 | 1.3% |

| 5. | Middle East | 2.1 | 16% | Under 1-m | 7.1% | 2.5% |

| 6. | Africa | 1.34 | 3.7% | 0.14 -m | 13.2% | 5.2% |

| Total | 52.6-t | 13.5- m | Av: 3.2% |

According to the CapGemini’s 2014 World Wealth Report, wealth it is led by North America [$14.8 -t], Asia Pacific [$14.2 -t], Europe [$12.3 -t], Latin America [$7,7 -t], the Middle East [$2,1 -t].

Africa’s HNWI

In 2014, Forbes’ annual ranking of the world’s richest people recorded 1,226 billionaires and 13.5-million HNWI. Of these, there were 16 African Ultra High Net Worth Individuals [UHNWI] who comprise a little over 1% of the positions on the Forbes list.

Of the 2-million HNWI who entered the rank last year with assets between $1-m – $5-m, Africa increased its share by 13.2% to 140,000 (0.14% of total).

Global HNWI Wealth is expected to reach $64.3-trn in 2016 and will continue growing at 6.9% a year across all regions, except Latin America. Asia-Pacific is set to overtake North America’s HNWI population and wealth by 2016 with a growth rate of 9.3%. Over the longer-term however, Asia’s tigers will be out-paced by Africa’s lions.

Growing Middle Class Consumers

Africa has the fastest growing middle class in the world comprising 313-m (34%) of its 1-billion population; a 100% rise in less than 20 years. Of this, 123-m are capable of spending $2.2 a day. By 2050, Africa’s middle class will grow to around 1 billion (42%) of its total population and represent 53.7% of the world’s consumers. They will require financial products and services to provide for rising needs in education, housing, transport, telecommunication, technology and protection of their household and business appliances.

The exponential and recursive impact of financing socially innovative technologies go beyond gains in intellectual property rights. Investments such as 3D printers in education, financing hybrid energy solutions for homes, re-fitting of fuel stations for electric vehicles and use of wearable devices in healthcare disrupts conventional ROI thinking and enables everyone in the value chain to play to their strengths.

Africa’s Middle Class Consumers

Youth demographics

The nature of the African market is distinctly different to Europe. Africa has a younger, more mobile market. Of the 1-billion people in Africa, 50 percent are under the age of 25. As children of ‘the unbanked’, they have very little education in financial services, lack a savings mindset and the majority are unemployed or work in primary and secondary industries. Of its adult population, two-thirds do not have a bank account or access to savings, credit or insurance. The disposable income required to consume such services includes costs for banking fees, transport, ICT infrastructure and electricity.

Innovative, Pan African financial products need to be designed to educate and cater for the continent’s youth, nomadic, migrant and refugee community. This is where Ecobank and M-Pesa are gaining a first mover advantage with technologies that enable users digital access to money, markets and products.

Says Judith Seekopp, a Swiss Banker and Wealth Manager, “Whereas the European market focuses on wealth preservation to cater for more mature, aging investors to secure generational wealth, Africa’s financial services products needs to have a stronger focus on wealth creation and tap unused wealth for start-up investments of young entrepreneurs on the continent.

Judith Seekopp

Digital Banking

The adoption of digital technology by wealth management firms in Africa has lagged behind the broader financial services industry. However, as digital connections ramp up among Africa’s youth, firms will have to adapt to provide integrated touchpoints which will enable stronger client relationships, reduce operating costs, enhance reporting systems and effectively deliver on its brand value proposition. The preference for digital contact in Africa is much greater compared to older clients in Europe.

According to the CapGenesis Global Wealth Report 2014, the global preference for digital is 26.4%, up from 23.7%; and is especially strong in Asia-Pacific (excl. Japan) at 37.8% and the Middle East and Africa at 33.5%. There is also an increasing preference for customized services (29.2% versus 26.0% a year earlier). This is especially strong in the emerging markets of the Middle East and Africa (48.2%), as well as Asia-Pacific (excl. Japan), at 36.7%.

Open Architecture

More investors are drawing on the expertise of local financial institutions than New York or Europe bankers to channel wealth into investments on the continent. In the past, wealth was primarily channeled offshore.

According to André Rangasamy of Wealth Planners, an investment advisory and financial planning firm to HNWI, there is increasing investor interest in Africa funds. “When constructing a global portfolio, the relatively low correlations between African equity returns and developed market returns make exposure to African equities particularly attractive. The ride may be bumpy, particularly over 1- 3 years, but this trend looks set to continue as the expected returns over the long term remain relatively attractive”.

To manage wealth across African countries, at various stages of economic development and socio-political systems, would require a Pan African approach to portfolio management with a wealth management network and open architecture product platforms. This would enable private banks to distribute products of other banks in exchange for a commission and not be restricted to selling only its proprietary products.

By using technology, wealth managers will better determine interests and contradictions quicker and develop more responsive strategies.

Says Judith, “Banks in Africa will attract more Euro-clients in the future as more HNWI invest on the continent. Open architecture systems will be needed. Also, they will require the proximity of a wealth manager on-site to enable access to tailor-made and traditional investment solutions at the level of quality, service and comfortability experienced by a UHNWI in Switzerland.

“The DNA structure of Swiss banking standards is the golden seal in wealth management globally. By blending South Africa’s technologically innovative banking system with world-class standards applied to socially responsible investments, new growth strategies can be unlocked. Quality, productivity and service delivery in wealth management are presently hampered in Africa without such innovation.”

Investment opportunities exist in infrastructure finance and corporate funding to facilitate Africa’s key growth sectors – agriculture, energy, finance, fishing, health, human capital, manufacturing, mining, technology, tourism and water. They present investors with early-stage investment opportunities.

To contribute to Africa’s leapfrog, innovative channels, products and services need to be designed that leverages its commodities, renewable energy and telecommunications systems for greater impact, sustainability and security.

Says Prof. Spies, “Such interventions, if well designed within a climate of social innovation, have recursive qualities to be the cause and the effect of transformative actions, thereby propelling a ‘snowball’ effect”. Eventually this momentum reaches a tipping point.

Extractable energy

Africa extractable energy resources (oil, natural gas, coal, and uranium) are worth between $13-14.5trn. In addition, there is around $762.4bn in net new money to be generated by untapped production potential in six key sectors – agriculture, water, fisheries, forestry, tourism and human capital. These provide scope for innovative investment products linked to IP (intellectual property) for institutional and private investors to benefit from exponential scaling using pricing models that are outcomes-driven.

Green comparative advantage

Renewable clean energy through wind, solar, hydro and biomass projects play a major role in sustaining Africa’s comparative advantage in the global green economy. With a 30 year history in solar innovation, it stands on par with the developed world. Mega projects are underway to develop solar and wind farms across the continent. This will enable Africa to increasingly delink economic growth from energy consumption and secure, clean energy supply to investment projects over the long term.

Philanthropy

The next generation of HNWI are ‘the millennials’ who have different social values. Those from the developed world will require guidance to manage significant inherited wealth and they will look for relationship managers who connect with their mindset. Currently, 75.0% of HNWI under 40 cite driving social impact as either extremely important or very important. However, the tendency declines about 10% with each age segment, reaching a low of 45.4% for those 60 and older.

Young HNWI recognize that one of the most serious threats to a sustainable world is global inequality in wealth and human competence. Today, some 85 percent of global wealth is owned by 10 percent of the global population. Empoverished people in Africa are caught in a low level human developmental trap largely because of their historical inability to profit from technological innovation.

Education and skills development in Africa therefore continues to strike a chord among HNWI who strive for social good. However, academic research proves that an innovative community cannot be ‘caused’ by developing skills or by more education. Rather, innovative societies emerge through cascading leadership and processes of infective social learning that lifts the confidence and status of members to apply, express and share their competence.

In the future, the inherent creative abilities of Africa’s youth needs to be tapped to encourage such endemic innovativeness. Using the paradigm of design thinking, the success of every-day problem-solving can be increased through this calculated, mapped out experiential learning process.

Technology and design innovation for sustainable tourism in Africa

Design is a bridge between creativity and innovation. It serves as a key source of differentiation, competitive advantage and value creation to drive economic growth. Historically, Africans have been unable able to exercise their own transformative power to produce value and thereby, wealth through design. Real development in Africa will only occur when its people are able to satisfy their own legitimate needs and aspirations in a meaningful way.

Untold Wealth

It is interesting to note, that at Blombos Caves in the Western Cape, the world’s earliest archeological evidence of design can be found in stone artifacts, clay pots and shell work depicting a 100 000 year design heritage. These contain locked-up knowledge on Africa’s ancient design code. Just as Steve Jobs created the Applemac on the code of Zen design, real African innovation will source its principles on this deeper foundation. Therefore, the master key to Africa’s future wealth is yet to be unearthed.

Blombos Caves: near Pinnacle Point in the Western Cape

Since the scramble for its resources began in the mid-17th century, Africa’s precious metals have found their way to the balance sheets of colonial empires and its people dislocated from its philosophy of wealth.

In the 21st century, it is poised to grow faster than the rest of the world with a greater ability to take stock of and account for its wealth. The time is opportune to build a scalable private wealth management industry at the service standards of the developed world in a multi-local way.